1851 England census return taken 31st March 1851

The certificate recording John’s first marriage to Elizabeth Brown shows that John’s father was a “Carpenter (deceased)” on 20th May 1839. It therefore seems that the most likely candidate for his baptism is as follows:

Baptism record of St Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney, London, Middlesex: “Baptism on 10th May 1818 of John, son of John, Joiner, and Hannah Mason. Born 23rd February 1818.”Further research has revealed at least two further siblings to parents John Mason and Hannah:

Baptism record of St Giles without Cripplegate, London, Middlesex: “Baptism on 2nd March 1817 of Henry William, son of John, Carpenter, and Hannah Mason of Fore Street. Born 23rd September 1816.”

Baptism record of St Dunstan and All Saints, Tower Hamlets, London, Middlesex: “Baptism on 27th January 1822 Hannah MASON daughter of John, Joiner & Carpenter, and Hannah MASON; born 26th March 1821.”The most likely marriage for this pair is that of John Mason and Hannah Doe at St Alphege, Greenwich, Kent:

“John Mason, Bachelor, of this parish and Hannah Doe, Spinster, of this parish, were married in this Church by license this 29th day of June in the year 1814 by me, J. P. George, Curate, in the presence of Ann Smith and J. S. Smith.” [Note: the witnesses were the same as the ones on a marriage following this one in the same church on the same day and therefore I doubt they are related in any way.]Confirmation of this marriage as the correct one comes from the 1851 census of England, placing the widowed Hannah Mason née Doe, living with her brother in Reading, Berkshire.

1851 England census return taken 31st March 1851

Further confirmation of the link is provided by the names given to the progeny of John’s first marriage to Elizabeth Brown, daughter of Timothy Ishmael Brown and Sarah. Elizabeth was baptised on 18th October 1820 at St Mary’s in Reading. John and Elizabeth were married on 20th May 1839 at the St Marylebone Parish Church at which time John’s occupation was described as “Upholster”. This ties in with the occupation of “Hair Worker” in the 1851 England census as this latter occupation reflects the upholsterer’s use of horse hair. The witnesses are “T. Brown” and “M. Wheeler”.

i. Elizabeth Sarah Mason born 2nd March1840 at 9 Charles Street, Marylebone, London

ii. Emily Mason born 19th September 1841 in 2 George Court, Marylebone, London

iii. Sarah Brown Mason born 3rd July 1843 in 2 George Place, Marylebone, London

iv. Hannah Maria Mason, born 14th June 1845 at 106 Broad Street, Reading, Berkshire

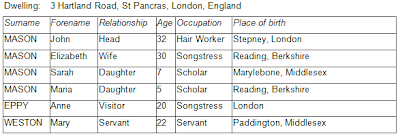

The table below contains an extract from the 1851 census of England that explains the whereabouts of the other two daughters:

1851 England census return taken 31st March 1851

We know that Elizabeth was alive on the 31st March 1851 from the entry in the 1851 England census. By the time John married for the second time on 3rd June 1852, he was described as a widower. I therefore assume that Elizabeth died between these two dates although no death record has yet been identified.

John’s second marriage was to Sarah Ann Paine at Old Church, St, Pancras, Middlesex on June 3rd 1852 at which time John’s occupation was described as a “Commercial Traveller” living at Hartland Road, St Pancras, London, as per the 1851 England census. His father is named as “John Mason, dead”. Sarah is described as a spinster living at College Street in London and her father is named as “James Paine, painter”. The witnesses to the marriage are “Annie Eppy” and “James Paine”. This “Annie Eppy” is presumably the same individual who was recorded as visiting in the 1851 England census.

From her death certificate, we know Sarah Ann Paine was born about 1826 in England. The 1851 England census confirms her place of birth as Bishopsgate, London.

Definitive evidence about the journey from London to Sydney of John Mason, Sarah Ann Paine and their four daughters has been difficult to find. There is one reference to a ship arriving in Sydney from England that seems an excellent candidate, mentioning as it does, “Mr. And Mrs. Mason, four children”. This is the ship Windsor that arrived in Sydney on the 4th November 1852. Taken together, the following articles and letters from publications of the time build up a timeline that corroborates this evidence.

“ENGLISH SHIPPING. The following vessels were advertised to sail from London and Plymouth for this port:- Windsor, July 21st” The Argus, Monday 11th October 1852

“SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE. The Windsor, Emily, and another full-rigged ship were at the Heads yesterday, waiting for Pilots.” The Argus, Thursday 21st October 1852

“The Windsor is originally from London, having merely called at Port Phillip for the purpose of landing passengers, who on their arrival were unanimous in expressing their acknowledgements in a handsome address to Captain Tickell, who has succeeded, in this his first voyage, in securing the esteem of all classes on board, as a proof of which, with only one exception, he has retained the whole of his crew, who have stuck by the vessel despite the attractions of the gold fields. The following is a summary of her cargo: 394 casks 4 cases brandy, 192 casks rum, 10 cases gin, 62 casks beer, 48 casks bottled beer, 6 cases perfumed spirits, 58 cases l8 casks Spanish wine, 160 cases Geneva, 60 cases porter, 15 cases whiskey, 59 cases French wine, 10 cases currants, 10 barrels 1 case 50 bundles raisins, 4 bales 1 case almonds, 4 cases plums, 300 sacks malt, 10 cases olive oil, 550 bags salt, 49 packages ironmongery, 5 barrels ginger, 5 cases cured fish, 23 coils rope, 1 case gloves, 1 cart, 1 case cordials, 415 packages sundries, sighted Mary Ann, at Gabo Island on the 31st ultimo. The Wild Duck and Emma cutters were in Twofold Bay on the 3rd instant; also sighted the Margaret, hence for Melbourne, off the Bay, same date.” The Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 4th November 1852

“PORT OF SYDNEY. ARRIVED. November 4.- Queen of the South, schooner, Stevens, from Gabo Islands. Windsor, ship, Tickell from Melbourne. Cheapside, barque, Lewis, from Melbourne.” The Argus, Monday 15th November 1852

“Captain Tickell.- To the Editor of the Age. There were two Windsors. Captain George Tickell commanded the ship Windsor, 800 tons, which sailed from Plymouth on 24th July 1852, and arrived at Melbourne on 22nd October, 1852, 89 days. She had a full complement of saloon passengers and seventy-six in the ‘tween decks. She left Melbourne on 27th October 1852 for Sydney. The other Windsor, ship, 1099 tons, made three voyages to Melbourne in the years 1853, 1855 and 1856. In the 1855 voyage she brought the 40th Regiment to Melbourne.” The Age, Saturday 4th August, 1934

This series of articles combined with information we already know about the family provides a useful timeline outlined below:

Event

|

Date

|

John Mason married Sarah

Ann Paine

|

3rd June 1852

|

Windsor departed London

|

21st July 1852

|

Windsor departed Plymouth

|

24th July 1852

|

Windsor arrived Melbourne

|

22nd October

1852 (89 days)

|

Windsor departed Melbourne

|

27th October

1852

|

Windsor arrived Sydney

|

4th November

1852

|

Annie Rebecca Mercy Mason

born

|

17th March 1853

|

We also know from their presence in the Australian records that John’s four daughters by his first marriage to Elizabeth Brown travelled with John and Sarah. While this evidence is compelling, it is not definitive. The passenger report for the Windsor in Sydney does not name steerage passengers. There may yet be a list of names as the article from The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser of Wednesday 10th November 1852 may have gleaned their information from an official source. The following is some additional information about the ship Windsor taken from Lloyd's Register:

Source

|

Lloyd's

Register of British and Foreign Shipping

|

WINDSOR

|

1851-1854

|

Master

|

Captain Pryce

(1851-52); Captain Tickell (1853-54)

|

Rigging

|

Ship;

sheathed in felt and yellow metal in 1852

|

Tonnage

|

676 tons

|

Construction

|

1835 in

London

|

Owners

|

R. Green

|

Port of registry

|

London

|

Port of survey

|

London

|

i. Annie Rebecca Mercy MASON, born March 17th 1853, Sydney

ii. Charles John MASON, born January 9th 1855, Sydney

iii. Lydia Sophia MASON, born March 30th 1857, Sydney

iv. James Vickers Arthur MASON, born October 12th 1859, Sydney

v. Clara Emily MASON, born January 23rd 1862, Sydney Only a few short years after the birth of Clara, we find John is admitted to Gladesville Hospital for the Insane. Gladesville is a suburb of Sydney located 9 kilometres north-west of the Sydney central business district. A major milestone in the development of the suburb was the establishment of the Tarban Creek Lunatic Asylum in 1838 on the banks of the Parramatta River. It was the first purpose-built mental asylum in New South Wales. In 1869 it became the Gladesville Hospital for the Insane. The medical casebook for John Mason shows he was admitted on 25th September 1868 aged 52 years. The following notes accompany his admission: “He is an Englishman a Protestant residing lately in the Glebe Sydney as a storekeeper married nine children the youngest seven years of age, he suffers from paralysis caused by injury to the head many years since, he is very melancholy and quickly frustrated and his position is one of the most critical, he is also ruptured.”Improvements in his health and strength are recorded over the following months but, in spite of this, the following is recorded in his notes on 31st January 1869: “His family have taken no steps to remove him, as it is quite impossible for him to ever regain a livelihood again - they perhaps avoid the burden of his maintenance.”There are sparse notes regarding his more or less stable condition in the following months until he is discharged to the care of his family on the 7th October 1869. On the 12th August 1870, John is once again admitted to the Gladesville Asylum with the following entry in his notes: “This is his second admission into this Hospital. The date of the former Warrant was Sept 25th 1868. Vide Ref 19. Folio 199. On admission his health has not improved by his residence at home, he becomes more feeble from general paralysis, he has much emaciated since he left this Hospital, he is cleanly and quiet.”His notes record that he regains weight but that his symptoms of “paralysis” do not improve. On the 19th August 1871, his notes indicate he is transferred to Parramatta Hospital. It is possible he may have been transferred via Parramatta Hospital but in fact we see him admitted to Newcastle Asylum for Lunatics and Imbeciles. Newcastle is situated 162 kilometres north north-east of Sydney. In 1867 the military barracks at Watt Street, Newcastle was converted to a Reformatory for Girls. In 1871 after much community protest the reformatory was closed and by 1872 converted to an institution for the intellectually handicapped. The first 120 patients came from Gladesville and Parramatta Asylums. From the patient numbering system in the admission records below, it seems likely that John Mason was one of these patients. Newcastle Asylum, Register No. 1 of Admissions, August 1871 |

Patient No

|

58

|

Name

|

John Mason

|

Admission date

|

1871 Aug 6th

|

Sex

|

Male

|

Age

|

55

|

Social condition

|

Married

|

Occupation

|

Nil

|

Nativity

|

England

|

Residence

|

Gladesville

|

Religion

|

Protestant

|

Mental Disorder

|

Paralysis

|

The Newcastle Asylum medical casebook shows John Mason admitted on 19th August 1871, aged 55 years. Extracts from his notes reveal a progressive worsening of symptoms.

“Not so well, appears more demented.” 28th February 1873Finally on 28th February 1874, following a prolonged period during which he is bed-ridden, the following is recorded in relation to John’s death:

“During month St Vitas dance has been very severe...” 30th November 1873

“Though weak and feeble is much better, the attacks of Chorea have subsided...” 31st March 1874

“Is emaciated though his appetite is ravenous.” 31st August 1874

“As usual until 13th at 8.20am was seized with a kind of fit and appeared dying. Sent for Medical Officer who then ... but died at 8.50. John Mason suffering from Chorea was suddenly attacked with brain disease and died this day February 13th 1875.”On the death certificate, the cause of death is described as “(1) Disease of heart (2) Unknown”. He was buried the next day at the Christchurch Burial Ground, Newcastle, New South Wales. The informant was the Superintendent of the Asylum. There is no evidence from the records that either Sarah or her children attended the funeral in Newcastle. Of course, I now know the unknown mental condition was certainly Huntington’s disease and with that knowledge, it is clear that John’s deteriorating behaviour and physical symptoms would have appeared like a form of progressive dementia or “paralysis”.

Sarah Ann died on the 17th April 1914 at 28 Mount Street, North Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, aged 87 years. The cause of death was given as “Senility”. Her father was recorded as James Paine, a Church of England clergyman, and her mother was listed as “Unknown”. The informant was her son Charles John Mason of 28 Mount Street, North Sydney. She was buried on the 20th April at the Gore Hill Church of England cemetery in Sydney. Witnesses to the ceremony were George W. Turner and Charles John Mason. She is recorded as having been born in Reading, England, married at St Pancras, Middlesex, England to John Mason at age 25, and living in Australia for 62 years. The death certificate lists two of her daughters as deceased and her living progeny as follows: “Charles J.” aged 59, “Lydia S. (Turner)” aged 56 and “James A. V.” aged 54.

.jpg)